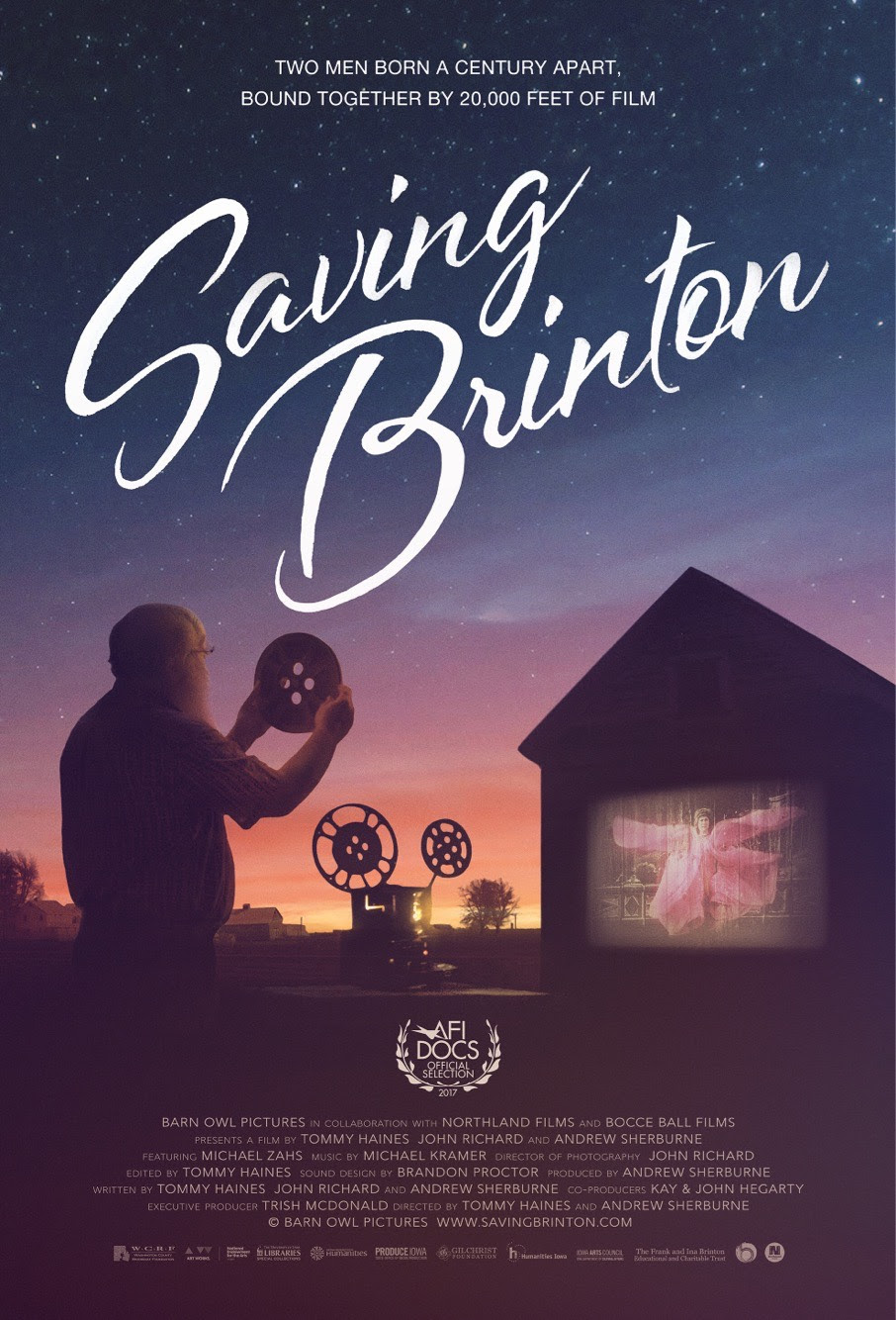

For many, going to the movie theater is all about escapism. Whether by some space odyssey, gut-busting comedy, biopic, family drama, or adventure historical, the movie theater is a place to depart the seriousness of life and embark on a journey of a different sort. Even with growing audience fallout, the theatrical experience remains a reprieve from the trials of the day-to-day, whether enjoyed in a proper cinema house or at home. For some, cinema is more than a series of moving pictures. For them, it’s a moment of history stuck in time; a product of its era encapsulated within a scant few frames of celluloid. It’s with this idea in mind that documentarians Tommy Haines and Andrew Sherburne craft Saving Brinton as they accompany collector Michael Zahs in his thirty-plus year journey to preserve the lost films of Iowa’s forgotten entertainers, The Brintons.

In the late 1800s, Frank Brinton and his wife, Indiana, toured the United States bringing with them entertainments of stage and screen. Before there were motion pictures as we know them today, Brinton used dissolving slide projections, black-and-white silent films, and even the rare colored films which required artists to hand-paint each frame to bring wonder and delight to the masses. When the Brintons passed, their manager took control of their vast collection until it landed into the hands of Michael Zahs, a history teacher, collector, and preservationist of Iowan history. After many years of trying to gain the attention of film organizations, Zahs first saw progress when Greg Prickman, a member of the Special Collections division within the University of Iowa, recognized the historical value of the collection in terms of local, national, and cinematic history.

For the general public, Saving Brinton isn’t going to turn heads, but, then, Saving Brinton isn’t for them. It’s for collectors, historians, cinephiles, and other preservationists. It’s a tale equally about the importance of protecting our past as it is about preparing for the future. Most of all, Saving Brinton is a study of Zahs, a man’s whose passion for his hometown gave him the constitution to advocate for these lost relics for decades. Haines and Sherburne do a wonderful job of not just following Zahs – a delightful and loving gentleman – as he goes from seminar to seminar educating the Iowan public about the Brintons, their advanced technology for the age, and their films, but also tracking his day-to-day to provide a dynamic sense of who Zahs is – a man devoted to the preservation of his community. Like the Brintons, Zahs is presented as a man with a great love for his hometown – he cares for the homestead that spent 300 years in his family, he gardens, attends livestock auctions, organizes alumni meetings for his high school, and visits elementary classrooms – and wants Iowans to be proud of where they came from. The Brintons used to show their films in the Graham Opera House, a Guinness record holder since April 2016 as the oldest active theater in the world. It’s a landmark that means very little to those outside Washington, Iowa, but it means a great deal to Zahs and preservationists like him. In one lovely moment, film historian Serges Bromberg is joyfully startled when Zahs shows him a previously lost work by French actor, director, and illusionist Georges Méliès (Le Voyage Dans la Lun (A Trip To The Moon)). These previously lost films aren’t going to create the audible gasps current blockbusters like Avengers: Infinity War elicits, yet there’s something innocent, something magical about the way Bromberg reacts to seeing scenes from Le Rosier Miraculeux (The Wonderful Rose-Tree). It’s a feeling akin to the realization of a love believed lost returning. As depicted by Haines and Sherburne, every person who engages with this lost material is overcome with undefinable joy as each new piece of the Brinton collection unearths a new piece of global, cultural, and cinematic history.

In a perfect summation of Saving Brinton, we’re shown Zahs speaking to a group of children about various historical artifacts and about how he loves to hoodwink his students into believing that they’re not going to learn anything since it’s not a traditional lesson. In many ways, that describes Saving Brinton to a tee. At no point are Zahs, Haines, and Sherburne lecturing the audience about the significance of the Brintons; rather, they present various aspects in a slow, patient fashion, highlighting the reactions of joy in each new bombshell discovery and demonstrating the various technologies the Brintons used that far exceeded the technology of the era. More than anything, watching Zahs’s face glow in delight by sharing the story of the Brintons with growing audiences slowly reveals the joy in learning. And just like that, before we know it, we’ve been hoodwinked into learning about something so niche, so utterly irrelevant to our daily lives, yet so significant in understanding our past that we, the audience, can’t help but smile, recognizing that the story we’ve just beheld is gift – a gift from Zahs that will stay with us forever.

For more information on the Brinton collection, visit The University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections page.

To find a screening near you, head to the Saving Brinton screenings page.

Final Score: 4 out of 5.

Find the latest details on Saving Brinton on Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | Website |